14. Fluid-structure interaction#

Michael Neunteufel

In this section we show how to solve a fluid-structure multi-physics problem. First, we will describe the involved equations, Arbitrary Lagrangian Eulerian (ALE) methods, interface conditions, and the problem of deformation extension. Then, two types of discretizing the fluid part are presented

Equations on fluid and solid

The Navier-Stokes equations with symmetric stress, velocity \(u\), and pressure \(p\) are considered for the fluid part

where \(\rho\) and \(\nu\) are the density and viscosity, respectively. For the solid we use the elastic wave equation with displacement \(d\) and \(P=F\Sigma\) the first Piola Kirchhoff stress tensor

where \(\rho\) is the density. We consider a St.Venant-Kirchhoff material law

with \(\mu\), \(\lambda\) the Lame parameters.

Navier Stokes in ALE (Arbitrary Lagrangian Eulerian) formulation

The Navier-Stokes equations are given in Eulerian form, whereas the elasticity problem is formulated in Lagrangian coordinates. Thus, to couple these two equations we use the Arbitrary Lagrangian Eulerian form (short ALE) for the fluid part, see e.g. [Donea, Huerta, Ponthot, Rodriguez. Arbitrary Lagrangian-Eulerian Methods. In: Encyclopedia of Computational Mechanics, 2004].

We will always work on a fixed reference domain. Therefore, we will transform the Navier-Stokes equations back to it. Let \(\Phi(x,t)=\mathrm{id} + d\) describe the movement of the mesh, where \(d\) is the displacement. Then we can relate the velocity on the deformed configuration \(u\) to the fixed configuration \(\hat{u}\) by e.g.

and use the chain rule

where \(F=\nabla\Phi\) denotes the deformation gradient. Next, we take the time derivative and get again with the chain rule

The time derivative of the deformation \(\dot{d}\) is called the mesh velocity and describes the relative movement of the mesh. Next we apply the transformation theorem, from where we get the determinant of the deformation gradient \(J=\det(F)\). With this the ALE Navier-Stokes equations read in weak form

Elastic wave equation as first order system

The elastic wave equation does not have to be transformed as it is already stated in Lagrangian form. We rewrite it as a system of first order equations in time by introducing the solid velocity \(u=\dot{d}\). The variational formulation is therefore given by

Interface conditions The interface conditions for fluid-structure interaction have also to be considered before we can couple the equations. The velocity and displacement have to be continuous over the interface and the forces from the fluid and the solid have to be in equilibrium

where \(\sigma^s\) and \(\sigma^f\) denote the stresses from the solid and fluid part, respectively.

As we are using a monolithic approach, where both equations are solved together in each time step, this equation is always fulfilled as a natural condition in weak sense as long as the deformation and velocity field is continuous over the interface. Therefore, we add both, the Navier-Stokes and the elastic wave equation, and then simply neglect the two force terms.

Deformation extension into fluid domain

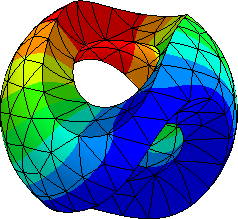

The last important ingredient is the deformation extension. The mesh velocity \(\dot{d}\) in the Navier-Stokes equations is artificial and has to be constructed from the given displacement of the solid on the interface. A very simple approach would be to solve a Poisson problem on the fluid domain with the solid displacement as dirichlet boundary conditions on the interface and homogeneous dirichlet conditions on the other boundaries. This works only for small deformations as the triangles might get pressed through others leading to a break-down. Thus, we will penalize the volume compression on the one hand and play around with a space dependent function to manipulate the stiffness of the problem, which yields a nonlinear elasticity problem with the material law of Neo-Hook

where \(h(x)\) denotes the space dependent function. The extension can have a negative effect on the elastic wave equations on the solid domain. Therefore, we multiply it with a small parameter to minimize this effect.